Building a Chess AI with Minimax and Alpha-Beta Pruning

Today’s post is all about the Minimax algorithm, and more specifically, using it to build a chess AI. This was an older project of mine, and having just created this blog, I thought it might be a good idea to go through how you might go about starting to design a chess AI to play against.

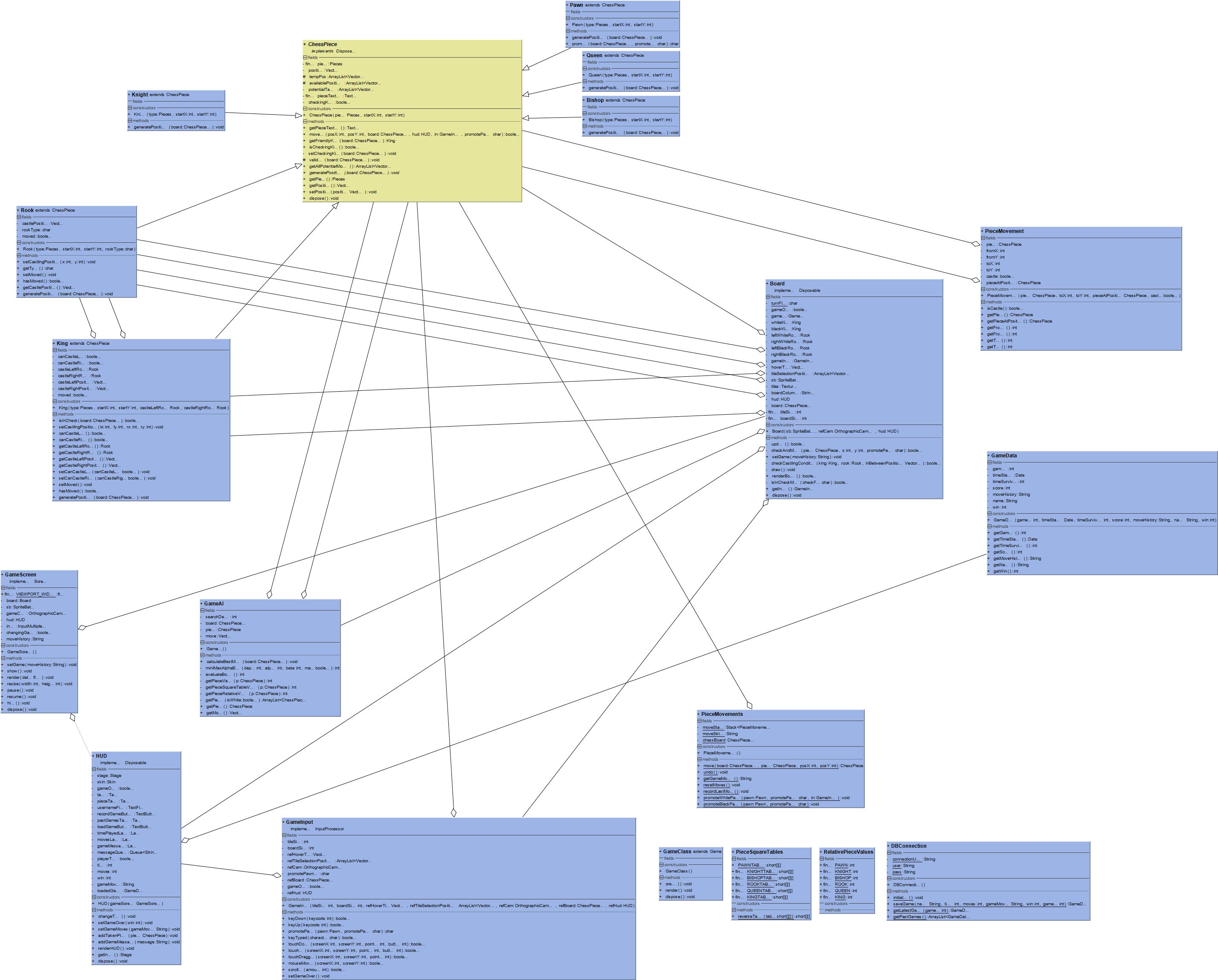

This was one of my larger projects, which involved building the chess engine first and then later implementing the decision-making functionality. I used Java and a library called LibGDX to do this, which is built on top of LWJGL. I had written a comprehensive writeup for this project back in high school with design, analysis, testing sections and so on. It’s quite a long read (100 pages), but I figured it could be a good reference. Here is the PDF, source code and UML diagram for good measure!

For this post, however, I’ll only be going through the algorithms I used to determine best moves. So, without further ado, let’s learn about Minimax.

The Minimax Algorithm

The Minimax algorithm is a type of recursive, depth-first search algorithm you’ll find used in decision-making and game theory. It’s mostly used in two-player, turn-based games to calculate the best possible next move. It does this by constructing a game tree where each node represents a particular state of the board. A node’s depth in this tree will represent how many steps ahead from the current board state it is. Each node(board state) can then be evaluated. Comparing the evaluations of the various board states allows the algorithm to choose the best possible move to make. Put a little more simply, the algorithm looks a few steps ahead in the game, at every possible scenario. One player will be assigned as the maximizer and the other player as the minimizer, each attempting to choose game states with the maximum or minimum evaluation respectively. The algorithm works with the assumption that a player will always make the most optimal move, and in turn account for the worst-case scenario.

Pseudo Code

Let’s take a look at some pseudo-code to see how this algorithm could be implemented.

function MiniMax(depth, maxi)

if maxi is true then

if depth is 0 then

return EvaluateBoard()

max = -infinity

for all moves

score = MiniMax(depth-1, !maxi)

max = MaximumOf(score, max)

return max

else

if depth is 0 then

return -EvaluateBoard()

min = +infinity

for all moves

score = MiniMax(depth-1, !maxi)

min = MinimumOf(score, min)

return min

Here, the function will return an immediate value for the leaf nodes at a depth of 0. And for nodes that aren’t leaf nodes, their value is taken from a descendant leaf node. The value of a leaf node is calculated by an evaluation function which produces some heuristic value representing the favourability of a node (game state) for the maximizing player. Nodes that lead to a better outcome for the maximizing player will therefore take on higher values than nodes that are more favourable for the minimizing player.

Minimax with Alpha-Beta Pruning

Alpha-beta pruning is an optimization on the Minimax algorithm to reduce the number of nodes evaluated in the search tree. It does this by no longer searching further down the tree when an evaluation is found that is worse than one that already exists. This allows for much faster computation and a higher depth search. It introduces two new values to be passed into the minimax function; alpha and beta. Alpha will represent the best current value for the maximizer, and beta will represent the best current value for the minimizer.

Pseudo Code

Let’s again take a look at some pseudocode to see how branches of the search tree can be pruned using this technique.

function MiniMaxWithAlphaBeta(depth, alpha, beta, maxi)

if maxi is true then

if depth is 0 then

return EvaluateBoard()

max = -infinity

for all moves

score = MiniMaxWithAlphaBeta(depth-1, alpha, beta, !maxi)

max = MaximumOf(score, max)

alpha = MaximumOf(alpha, max)

if beta <= alpha then

break out of loop

return max

else

if depth is 0 then

return -EvaluateBoard()

min = +infinity

for all moves

score = MiniMaxWithAlphaBeta(depth-1, alpha, beta, !maxi)

min = MinimumOf(score, min)

beta = MinimumOf(beta, min)

beta <= alpha then

break out of loop

return min

With these few additions, we can see how the number of nodes evaluated will be reduced. By breaking out of the loop, we are leaving the algorithm to only consider nodes with the potential of containing better evaluations than already found. This is where the improvement in computation comes from. You can see the testing section of my write-up to see comparisons of using Minimax with and without alpha-beta pruning and improvements in execution time at different search depths.

The Evaluation Function

If we consider all the different configurations of chess pieces on a chessboard, we find that the number of combinations is far too high to store a value for each state. Therefore, pre-determining the relative value of any state of the board is impossible. So, instead, we can use an evaluation function. These are some of the most important variables:

- Material - The sum of piece values for each side.

- Relative piece values - A value assigned to each piece when calculating its relative strength in comparison to another piece.

- Mobility - A measure of all legal moves that can be made in a given state of the game.

- King safety - An evaluation of how safe the king is in any given state of the board.

- Piece-square tables - A way of assigning specific piece values to specific board positions.

There can be many aspects to determining the value of a state of the board, but for this project, I only included the use of material, relative piece values and piece-square tables.

Pseudo Code

function EvaluateBoard()

total = 0

for all pieces on the board

total += GetPieceValue(piece)

return total

function GetPieceValue(piece)

value = 0

value += PieceRelativeValue(piece)

value += PieceSquareTableValue(piece)

if piece is white then

return value

else

return -value

The EvaluateBoard() function works by summing every piece’s relative value with its square table reference on the board. White pieces would return positive values and black pieces would return negative values. This in total results in a unique evaluation of the board in that state.

Conclusion

Creating a chess AI can get much more complicated than this. Implementing deep learning models would be an example. However, in the case of games like chess, go and tic-tac-toe, often the hard-coded symbolic AI approach is enough. This same algorithm with its alpha-beta counterpart was used by IBM’s Deep Blue to beat the world chess champion, Garry Kasparov. AI has taken a much more interesting approach since the days of Deep Blue. Machine learning tackles problems from a completely different angle. It is also another passion of mine, so do expect future ML related posts. In the meantime, thanks for reading!